Drayage operators working the ports of Los Angeles-Long Beach and Oakland are entering 2023 facing a new clean-truck regulation banning older trucks that comprise almost one-fifth of the existing fleet from California’s ports, but drayage capacity should not be immediately affected amid declining import volumes.

Drivers are also navigating moves by state agencies to begin enforcing the state worker classification law known as AB5.

California’s clean-fleet regulation that took effect on Jan. 1 bans about 4,000 drayage trucks with engines of model year 2009 or older from entering the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, or about 16 percent of the registered drayage fleet for the largest US gateway, according to the ports. A port spokesperson in Oakland said about 19 percent of the drayage fleet there is affected.

Still, the actual impact of the new regulation should be minimal, at least in the short-term, given that import volumes in Southern California have been declining by double-digit percentages since September due primarily to a loss of discretionary cargo to East and Gulf coast ports as coastwide contract talks between the International Longshore and Warehouse Union and terminal operators show no sign of resolution. The National Retail Federation is projecting double-digit declines in US imports nationally at least through April as the economy softens and inflation and interest rates remain high.

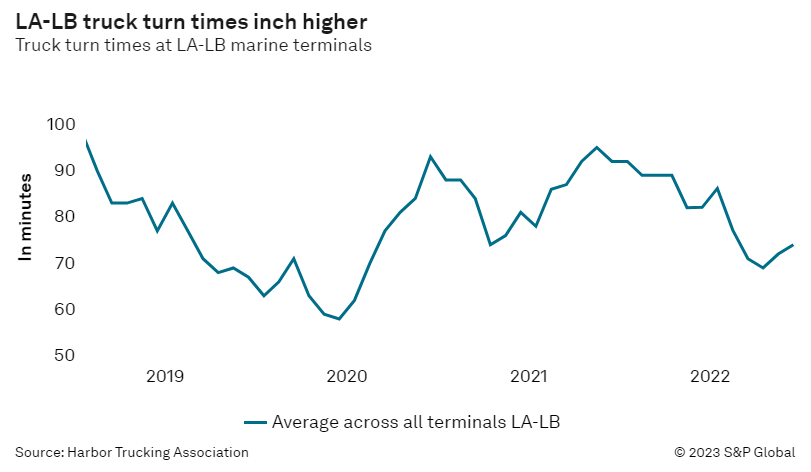

Truck turn times in LA-LB, while up marginally in December from November, remain down sharply from last summer.

“It’s too early to tell what impact — if any — this would have on drayage operations,” Noel Hacegaba, deputy executive director of administration and operations at the Port of Long Beach, told the Journal of Commerce Tuesday.

Terminal operators in Los Angeles-Long Beach are enforcing the clean-fleet regulation by using radio-frequency identification (RFID) technology to ensure every truck in the ports’ drayage truck registry is compliant before allowing access to their facilities, Hacegaba said. Oakland uses its “Secure Truck Enrollment Program” to register trucks and manage the clean-truck program, although terminals are not equipped in real-time to prevent non-compliant trucks from entering, the port spokesperson said.

AB5 enforcement in the spotlight

Meanwhile, a pickup in enforcement activity around AB5 has occurred in recent weeks, said Chris Shimoda, senior vice president of government affairs at the California Trucking Association. That includes involvement by state agencies such as the California Division of Labor Standards Enforcement and the Employment Development Department, as well as notices sent to trucking companies involving unpaid wages and benefits sent by private attorneys representing drivers.

“We’re starting to hear this is happening. I just got a notice today involving a company,” Shimoda said on Wednesday.

AB5, which ends the use of independent-contractor drivers that have dominated harbor drayage nationally for the past 40 years, will have a permanent impact on how harbor drayage is conducted at California’s container ports. Some trucking companies have established brokerage operations in which hundreds of former owner-operator drivers are now contracting directly with drayage companies as licensed motor carriers (LMCs). Other trucking companies are converting to employee-driver models, while some have hybrid operations with both brokerage and employee-driver units.

Matt Schrap, CEO of the Harbor Trucking Association, said his members in both Southern and Northern California have been responding to the implementation of AB5 since the Supreme Court decision last summer upholding the legality of the California law.

“Everybody knows it’s there and they’re changing to the brokerage and employee-based models,” Schrap said.

The biggest challenge that drayage companies and former owner-operators face is that there are no definitive guidelines to define compliance, Schrap said. “We need to have a clear path forward so operators can run their businesses,” he said.

Source: Journal Of Commerce